Why The Human Factors of Aviation Maintenance Matter

Our A&P tells you about ‘The Dirty Dozen’ and why each of them is so important.

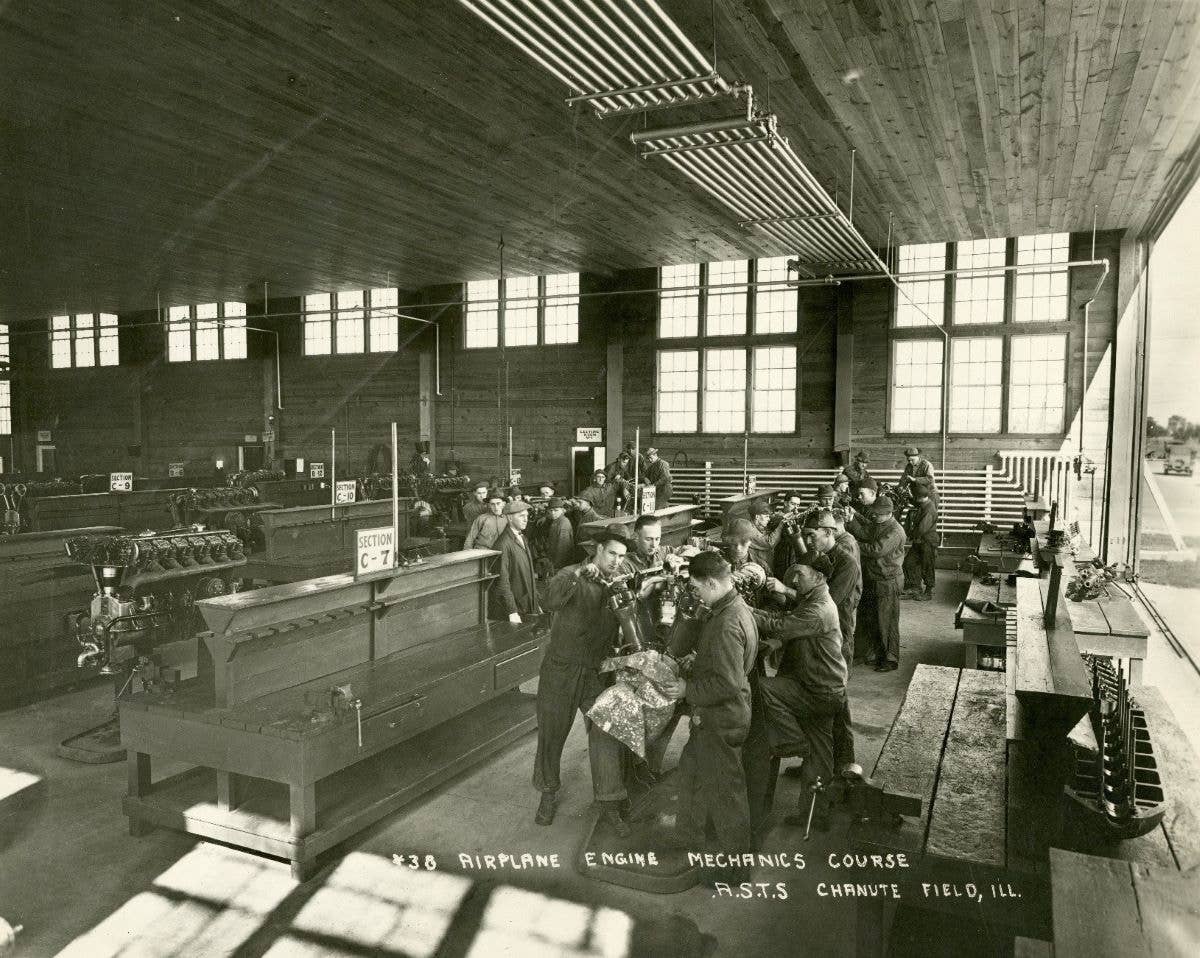

Frequently, aircraft maintenance professionals are placed in uncomfortable situations when maintaining aircraft. [Courtesy: Richard Scarbrough]

The alarm sounds at 0605 local, and I barely register that I am alive, let alone awake. Struggling to my feet, I dress and move slowly toward the kitchen, where my mother greets me with a red-and-white 16-quart Igloo Playmate cooler, packed with all three meals I would need for the next 18 hours and snacks. I shoulder my faded black Jansport backpack, hoist my Sears Craftsman toolbox into the truck, and fight to stay awake on my early morning drive to airframe and powerplant (A&P) school.

A&P school concludes at 1500. Next, my shift starts at the ATL T Gates. As a mechanic’s helper, my duties ranged from interior cabin work to hauling Lockheed L-1011 tires and nitrogen bottles. We sometimes entered aircraft logbooks into the computer.

Yes, I am L-1011 years old.

The second shift on International Line Maintenance ends at 2300, time to clean up, gather tools, and board the crew bus for the parking lot. It will be well past midnight before my head hits the pillow, and it will hit hard.

At 0605 the following day, it starts all over again. Lather, rinse, repeat. One weekend a month, I rise at 0505 and report for my U.S. Naval Reserve duty at Attack Squadron (Atkron) VA-205 on Naval Air Station (NAS) Atlanta. Monday morning, it begins again.

The above scenario was my life for three years. It is not a sustainable schedule for an aircraft mechanic. I was also one tired human, and that factored into my work. The human factor—hey, we may be onto something here.

A Short History of Human Factors

Studying human factors has roots in the 1940s, but it was far from the buzzword we recognize today. What are human factors anyway? The FAA defines human factors as a “multidisciplinary effort to generate and compile information about human capabilities and limitations and apply that information to equipment, systems, facilities, procedures, jobs, environments, training, staffing, and personnel management for safe, comfortable, and effective human performance.” (FAA Order 9550.8A)

I can tell you that in 1991 I never heard, nor was anyone aware, that the study of human factors existed, let alone carry the importance it does today. Working long hours was just something you did to get ahead. Not a soul ever asked us if we were too tired to work on airplanes, and doubtful any of us would admit it anyway. When I was in AMS A School in Millington, our battle cry was that we should sleep when we were dead, and we will still pull duty and stand watch.

Frequently, aircraft maintenance professionals are placed in uncomfortable situations when maintaining aircraft. Not every job is at 1000 on a Tuesday in a climate-controlled hangar. Airplanes are fickle and will break whenever it pleases them. They usually fail in a remote location, at night, while cold and rainy, with an angry owner blowing up your phone. Or so I have been told.

The early ’90s was a time for significant changes in aviation. Some of the old legacy carriers ceased operations, like Eastern Airlines, Pan American World Airways, and Midway Airlines, just to name a few. Some airlines have struggled to compete in the new world for a little over a decade since deregulation. Other changes were on the horizon, as well. Gordon Dupont developed a system for recognizing 12 human error elements that contribute to unsafe conditions in the great white north at Transport Canada. The Dirty Dozen makes its way worldwide, evolving and adapting to specific missions as needed.

In November of 2012, the FAA Safety Team published content about the Dirty Dozen in this infographic.

Continuing on the work started by Mr. Dupont, the FAA sought to arm pilots, safety representatives, and mechanics with the knowledge and tools needed to navigate aerospace’s tricky landscape.

The Dirty Dozen?

The Dirty Dozen contributing factors or preconditions to human error are:

1. Lack of Communication

This topic is number one for a reason. Effective communication is the cornerstone of every success story. Expand the method of communication beyond verbal, use a checklist, and use call and response if necessary.

2. Complacency

One should expect to find errors, and do not assume something is airworthy just because it flew in like that. Unlike the judicial system, airplanes are grounded until proven airworthy.

3. Lack of Knowledge

Carl Sagan remarked, in The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark that, “every question is a cry to understand the world.”

Training is your best defense against a lack of knowledge. If you are unclear on a task or maintenance action, please raise your hand.

4. Distractions

A recent AAA study shows that odds of a driver being involved in a crash nearly doubled when they were engaging in all visual-manual cellphone tasks taken together and more than doubled when they were texting.

How often have you been knee-deep in a project, only to have your mobile phone ring just as you were about to set a critical piece?

Keep tabs on your work progress and retrace your steps if necessary.

5. Lack of Teamwork

There is no “I” in a team, but people often like to hoard information, feeling like it makes them irreplaceable. This action was especially true in older generations, who mainly operated on tribal knowledge.

The underlying thread of teamwork is trust. A solid team should strive to make each other better, thereby ensuring success for the mission.

6. Fatigue

I was one tired human and survived because I was in my early 20s, hungry for work, and coffee in the line shack was jet black and free. Fatigue applies to mental and physical exhaustion. But I was not bringing my best self to my work.

Use the buddy system to cross-check each other before calling for inspection.

7. Lack of Resources

Enlist in the Navy and learn all about the lack of resources. Air Force types can skip this part, as it will seem a foreign concept to you. All kidding aside, a resource could be a tool, technical publication, spare part, or even lighting in the hangar. You cannot inspect what you cannot see.

Plan your work ahead of time to ensure all the pieces are in place to perform maintenance.

8. Pressure

Ever heard: “Sign it off and taxi out. We have a full bird and a departure deadline to meet”? Again, physical, psychological, and mental pressures are at play here. Never be afraid to say, “No, I am the deciding factor, and this bird is not going.”

9. Lack of Assertiveness

If you lack the assertiveness to perform proper maintenance, find another line of work. There is no place for a job half done in aerospace.

10. Stress

Take breaks. Tell the boss that breaktime is necessary to realign your chakras, but please don’t burn incense in the hangar; they will drug test you for sure.

11. Lack of Awareness

What do you mean there is a difference between inch-pounds and foot-pounds? I just set any torque wrench I have handy to the number 35.

Read the manuals first! Once you have a clear path forward and the necessary resources, only then open the toolbox.

12. Norms

The kiss of death during any inspection is: “Not sure; that is just the way we have always done it.” Passing down bad habits is a thing. Break the cycle.

Challenge the status quo; only don’t get crazy.

You have the Dirty Dozen now, with a bit of color commentary from yours truly.

Human Factors in MROs

The role of human factors in aviation organizations, especially those that perform aircraft maintenance, is crucial to the entity’s success. It is also most likely to meet resistance from the people with the most to gain. Aircraft folks may be “old school” and not have time for newfangled ideas that take up time and create more forms to fill out.

I spent some time with Sam Lee at Integra Aerospace Ltd trying to get to the root cause of the matter. Why are some aviation maintenance types so averse to change, even if the change helps them?

“From my experience, the one most significant challenge that maintenance repair and overhaul (MRO) shops have is making human factors relevant and providing tangible individual value to those participating,” Lee said. “They find the training mundane and often feel like they are just ‘tick-in-the-box’ and cannot see the benefit.”

When we discussed ways to solve this, he said: “The answer to this is to make it relevant through activities that get the participants to investigate the human factors that directly affect them today and their influence on their unique work environments and role. Also, use scenario-based activities that use occurrence reports to illustrate real-life events relevant to that organization.”

Scottish philosopher David Hume once said, “Human Nature is the only science of man; and yet has been hitherto the most neglected.” I interpret that to mean that we go to great lengths to preserve these incredible flying machines in our charge, scrutinizing the most minute detail. Yet, when it comes to our own physical and mental health, we are quick to circumvent established parameters and may even act recklessly.

Don’t be that person. Raise your hand, ask questions, and take breaks. Read the manual. And please leave the incense at your hippy cousin’s house.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox