The Ercoupes had electric starters, greater fuel capacity, 75-horsepower engines and not-so-great condenser-tuned radios. Joel Kimmel

In 1948, living in New Jersey, I wanted very much to get into flying. My inquiries led me to Secaucus (now a metropolis in its own right, 10 minutes from New York City), where I found the Dawn Patrol seaplane base located on the Hackensack River. The owner-operator was a veteran Navy pilot, who just a few years earlier had engaged in combat flying a torpedo bomber. His name was Cliff Umschied, and the fleet consisted of two Luscombes on floats. I was a kid and didn’t have much money at the time, but it was the beginning of a long and wonderful love affair with aviation. The lessons that my own flight training taught me stayed with me over the years until I eventually became an instructor and a designated pilot examiner.

Fast-forward to the Korean conflict that erupted in 1950. The following year, I found myself at Naval Air Station Barber’s Point on Oahu, Hawaii—about 15 air miles from Pearl Harbor—having completed several rounds of technical training, though I still wanted to fly. One day, I took a bus that made a stop at Honolulu International Airport (KHNL), now David K. Inouye International Airport, and there discovered the Hawaiian School of Aeronautics, owned and operated by a very pleasant woman whose husband at the time was a colonel fighting in Korea. Her name was Marguerite Gambo Wood, chief flight instructor and DPE. The fleet, as I recall, consisted of four Aeronca 7AC Champs, two Ercoupes and a Seabee. My instructor was June W. Johnson, a young lady probably not more than six or seven years older than I was.

June told me that her husband was a pilot for Hawaiian Airlines, then a freight carrier for the islands. We did air work over the pineapple fields—the same ones flown over by the attacking Japanese planes 10 years earlier—and pattern work mostly at Bellows Field, an abandoned World War II base on the east side of the island, not far from Kaneohe. We got by in a Champ with no electrical system at an international airport with 10,000-foot runways and four-engine traffic going on all day by using the light-gun system. We taxied out to a pad that was monitored by the tower, and when he flashed his light, we acknowledged by wagging the ailerons and elevator. Returning to the field, it was a right downwind with the ocean on our left. We watched the tower for their signal and rocked our wings to acknowledge. After just a few hours, I was signed off for solo and encouraged to go up and do stalls and spins at will.

Check out our new content: I.L.A.F.F.T. Podcast

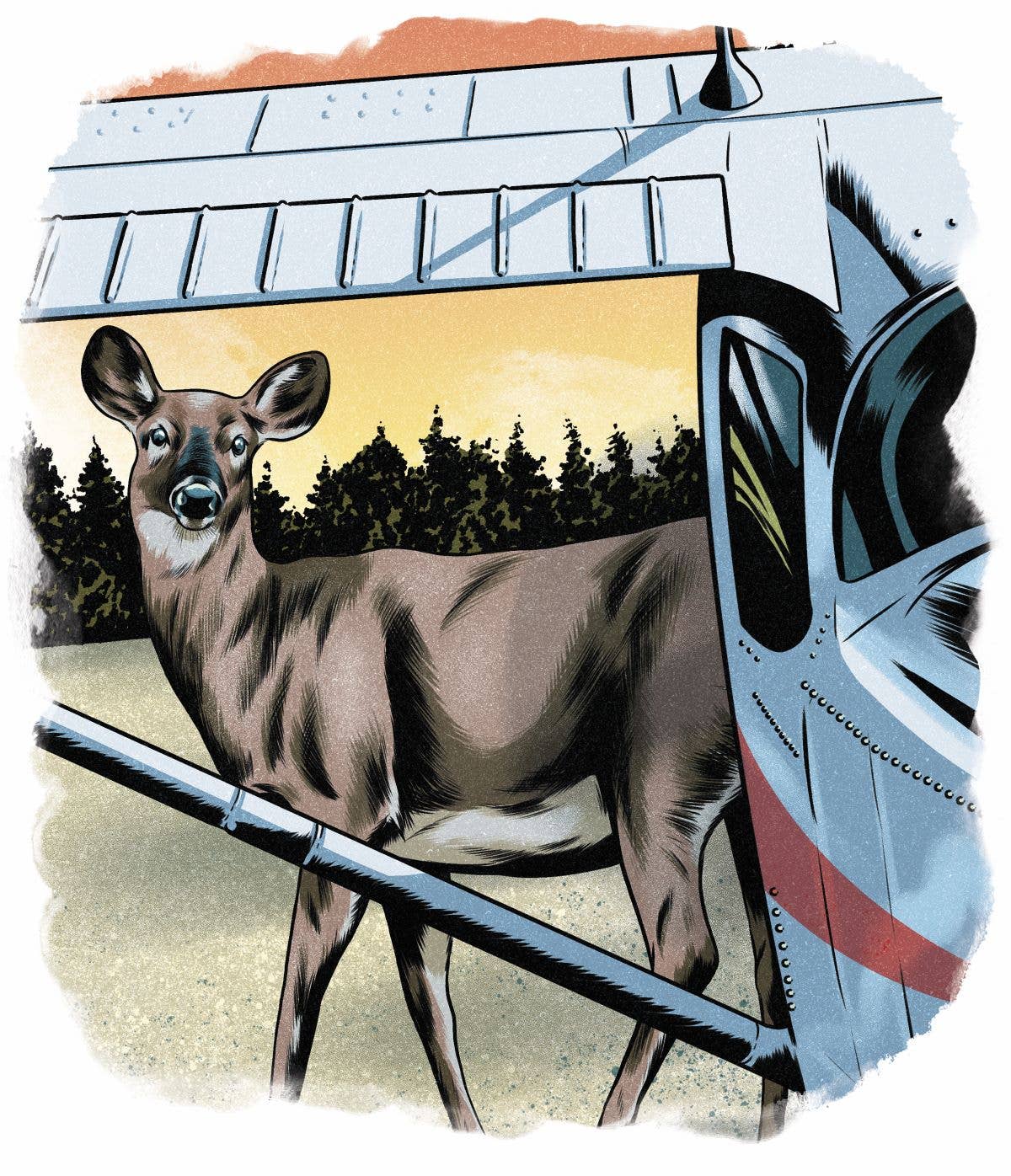

But by far the most challenging and memorable period for me was fulfilling the cross-country requirements. That’s what the Ercoupes were for—flying to the other islands. They had electric starters, greater fuel capacity, 75-horsepower engines and not-so-great condenser-tuned radios.

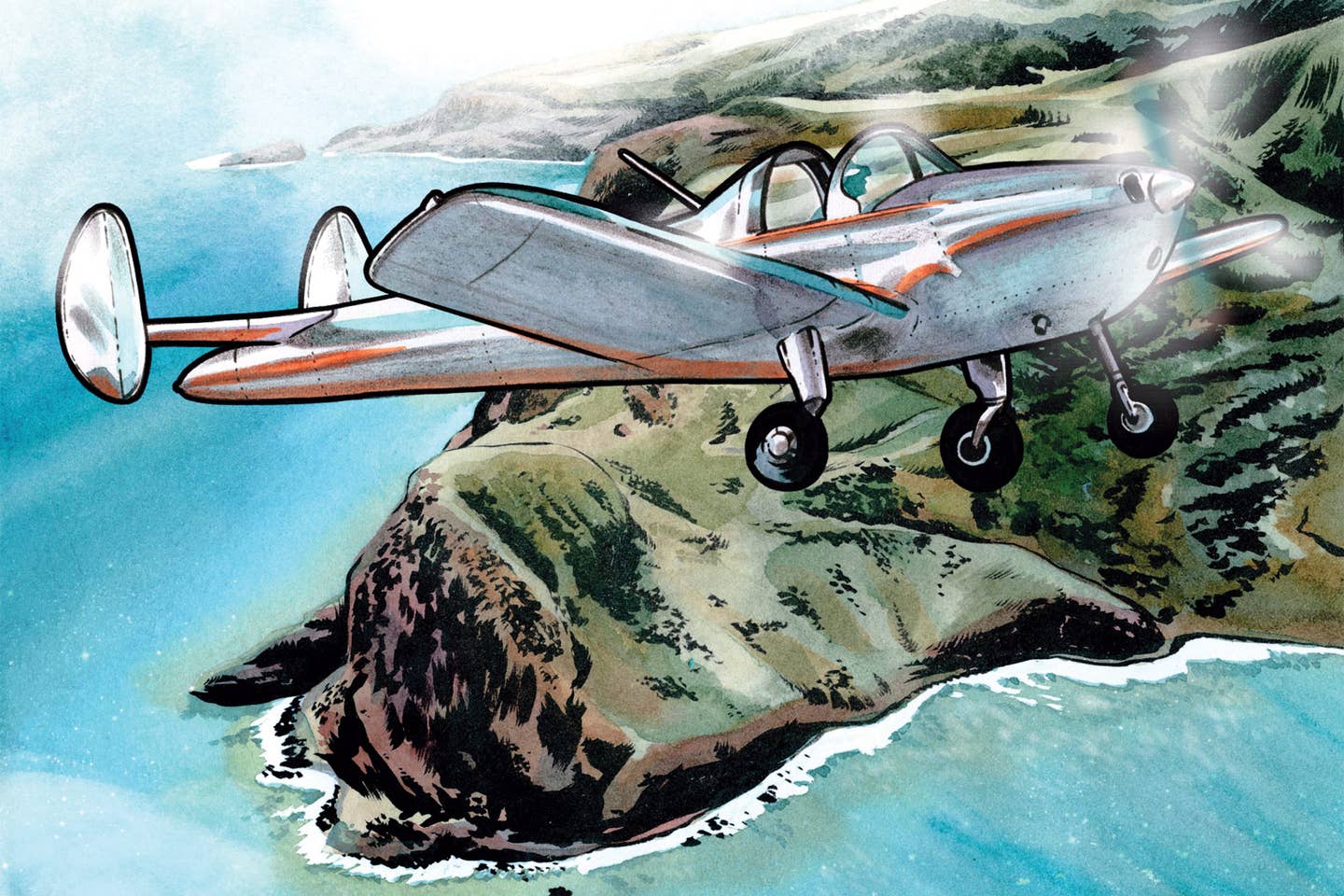

I flew the cross-country once with June and a second time alone. The flight took us from KHNL to Diamond Head at the southeastern tip of Oahu, then across the channel to Lauu Point at the western tip of Molokai, landing for a pit stop and verification signature at Molokai Airport.

Sounds simple enough, but it entails flying over what is serious open water for about 30 nautical miles in an Ercoupe with a questionable radio. Then it was off to the north coast of Molokai, a route that took us to the second required landing at Kahului Airport on Maui. The route ended with flying south to the coast of Maui, then back west to Lauu Point and home.

In the ’60s, we moved to Westchester County, New York. On weekends, I freelanced as a CFI at a small field in Duchess County (I taught my youngest son to fly on those weekends) and used nearby Westchester County Airport (KHPN) every chance I could. At 57, I left the business world and began 10 years at KHPN as a flight instructor, chief flight instructor and, for several years, designated pilot examiner for the local FSDO. I never forgot the skills I acquired over the pineapple fields on Oahu in the little Champs.

Read More: I Learned About Flying From That

On one of the last flight tests sent my way, a fellow instructor referred a young gentleman who had completed the private pilot training requirements. After the preliminary logbook check and oral exam, we went through the preflight and then did a couple of landings—they met the standards. We then left the pattern, and I directed my applicant to a work area nearby, telling him that we were going to do some stalls and steep turns. Now, many applicants for a flight test exhibit some nervousness, and I’ve always believed that a reasonable examiner makes allowances for that, but his reaction was quite visible.

We cleared the area, and I told him to do a gentle no-flaps stall and recover at the first sign of a break. By that time, judging by his demeanor, I’m sure he was in a sweat. I had him do a couple more clearing turns to help settle him down and then told him to do a full-flaps stall with a full break and recovery with minimum altitude loss. The result: left wing well down, controls crossed, and we were in an incipient spin. Had he been alone, he would have died. I recovered (shades of my early training in Oahu), suggested that he relax, and headed back to base.

In our discussion afterward, he told me that he hated stalls. I asked him how many stalls he had done in his training. His response: “Three.” (Mental note: Mention to the instructor the importance of completing requirements before recommending a flight test.) To the applicant’s credit, he retrained with his instructor, overcame his fear and came back to me for a retest, leaving happily with his private ticket.

When unpacking our things after the move to Westchester County, I came across a box of some old records, and sure enough, among the items was the 1951 Hawaii sectional, the very chart I used for the cross-country flights—course lines and all. Given the layout of the islands, it’s a very big sectional—a good 5 feet long and about 18 inches high. It has been framed and hangs on the wall of my “cave” over my desk. Every day, it brings back the joy I had flying in beautiful, pristine Hawaii. I was a fledging at the time, but the challenges it presented and the education it provided lasted a pilot’s lifetime.

This story appeared in the March 2021 issue of Flying Magazine

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest FLYING stories delivered directly to your inbox